Potherder.

Operating traps for seven years @DTAG.

It’s been seven years now that I started to contribute to the setup of Deutsche Telekom’s Early Warning System which is running multiple honeypots all over the globe and I would like to share my personal view on the history of the project, its internal goals and its achievements.

I still remember the first group meeting with my department in November 2010. It was my third day at the new employment in the team “Security of Office and Portals” and I happened to start my new career path all dressed up, because I thought this was the way to go in a large corporation. Turns out I was wrong about this, some people were more technical than I initially thought and it took some time to lose the first impression I made wearing a suit …

I was really curious when during the meeting one of my new colleagues presented on the current status of their internal web honeypot project, which had been running for the past six months. The four people involved in this next-to-dayjob-research project (@schmalle, @trixam, Lutz and Rainer) were running glastopf, a web honeypot to capture attacks like LFIs and php command injection attempts. They were presenting to the group how glastopf worked and the observations they had made within the last 6 months. During my previous employment at the governmental IT security organization, I had already gathered some experience with honeypots as one of my fellow colleagues was the author of a honeypot daemon, honeytrap. So, I felt this was something fun and asked if I could contribute to this project. And luckily, I was encouraged to do so…

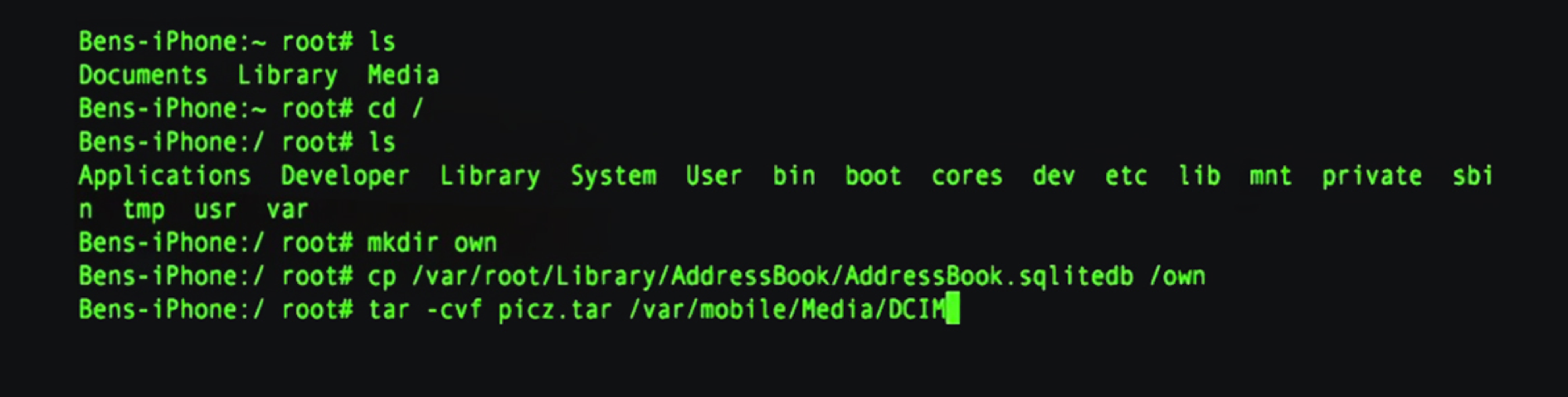

As DTAG is also a mobile network provider, my first assignment in the beginning of 2011 was to research what kind of network attacks smartphones on our network are exposed to and therefore develop a smartphone honeypot. I already played around a little bit with kippo, a medium interaction honeypot which mimics SSH terminal sessions. It is hilarious to see attackers being trapped and fooled by the honeypot in real time. So, I decided to adapt the code of kippo and the filesystem layout in order to behave like a jailbroken iPhone and a rooted Android phone and see if I could catch any device-specific attacks. After setting it up and connecting it to a 3G business APN (as regular mobile users have a carrier grade NAT), I was ready to capture device-specific attacks on my pretended smartphones. And I did indeed capture some device specific attacks: For example, one attacker who connected with the iPhone specific combination of root:alpine directly navigated to the DCIM folder of the iPhone and tried to steal the photos as well as the address book off the phone. So, there it was, our first mobile specific attack.

While I was working on the mobile honeypots, my colleagues were busy setting up new honeypot daemons like dionaea or honeytrap and had developed a backend application which served as a central data storage for honeypots data. We implemented an own transmission format, we called ews xml, which was derived from the Intrusion Detection Message Exchange Format, IDMEF. For each honeypot, a script would take care of the log-parsing and extraction of information that was of value for us. As an ISP, we were mostly interested in IP addresses of our customers, so we could hand them over to our abuse department, which in return could inform the customers about possible malware infections. The process had to be fully automated, so our backend needed to implement the logic of determining IP addresses belonging to us and adding context information. As a byproduct, we were able to inform other ISPs and partners about malicious traffic from their IP ranges. And for the first time, our small honeypot project was able to contribute statistical information about attacks on the honeypots to DTAG’s cyber security report. That’s when other international DTAG subsidiaries became aware of what we were doing in headquarters.

This year, I also made first contact with The Honeynet Project, a non profit organization which drives researches in the field of attack detection using honeypots, by attending to their annual conference in Paris. Although I already knew some of their members, I was able to get in contact with honeypot developers in person, whose software we were using. Very skilled people, what a great experience.

In the beginning of 2012, we were got the chance to present our honeypot network including the automated attack processing at DTAG’s huge booth at Cebit, Germany’s largest IT fare. I repeatedly presented our system to interested audiences, from students to C-level executives of other companies. It was the first time that we publicly demoed DTAG’s honeypot network. My personal highlight were the five minutes I spent talking to DTAG’s then CEO René Obermann, a very friendly and charismatic person. When he visited our exhibit, he was already briefed by his staff and asked some detailed questions about our processing and our evaluation of the attacks. Apparently, we did a good job and he was excited about the stuff we achieved with such a small team with very limited resources, next to our day job. This meeting granted us a lot of management attention and subsequent backing over the next years.

Back then, we had like 40 honeypot installations, mostly in Germany and around 40.000 attack events per day that we processed. Next to new honeypot technologies, we also played around with mod_security running on productive applications as data source and connected it to our backend. Back then, the backend consisted of a grails application with Elasticsearch and a mongodb as data storage, something we would not touch until fall 2017. We also implemented our first API which would use the information stored in our backend: A blacklist API which returns all IPs that have been maliciously active in our honeypots within a 2 hour timeframe.

It was also in 2012 when Markus developed his first own honeypot daemon, mysqlpot which was able to capture attacks on the mysql protocol. You need to know, although he is a vice president at DTAG, he loves to play around with new technologies in his spare time and always creates useful stuff using new technologies. Also in this year, as the smartphone honeypots were running for quite some time, we evaluated the results and published an article in Germany’s leading IT magazine c’t. The experience we gathered was further incorporated in another research paper, together with scientists researching a similar topic.

When my wife put a Raspberry Pi in my Advent calendar this year, I was thrilled and immediately played around with it. It was such a small device, capable of being driven by a battery pack, yet powerful enough to run network based services. For fun, during my parental leave, I managed to compile honeytrap on ARM and code a piece of software to drive a serial display which I attached to RPI’s GPIO. I then attached a 3G modem to it and connected it to the mobile internet. Finally, we had our first ARM-based portable honeypot, internally called “semtex” as it looked like some kind of explosive, which had a display on it showing how many attacks it captured and who was the last attacking IP. Again, this device was highly appreciated by the management, because it simply showed the number of attacks against the device. It was easy to comprehend, even for non-techies, and made something virtual like a honeypot into something you could see and grasp.

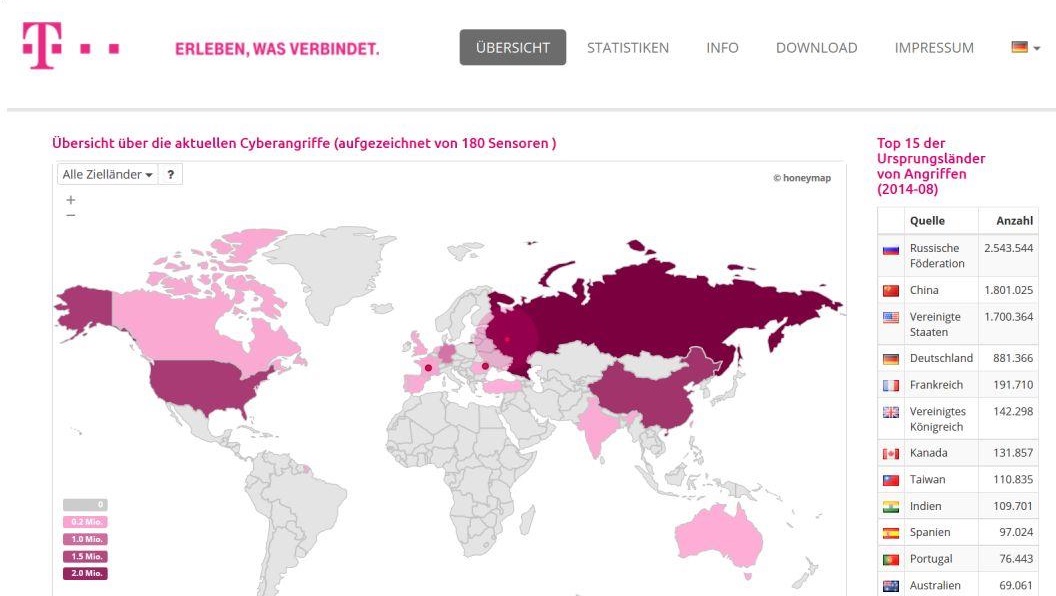

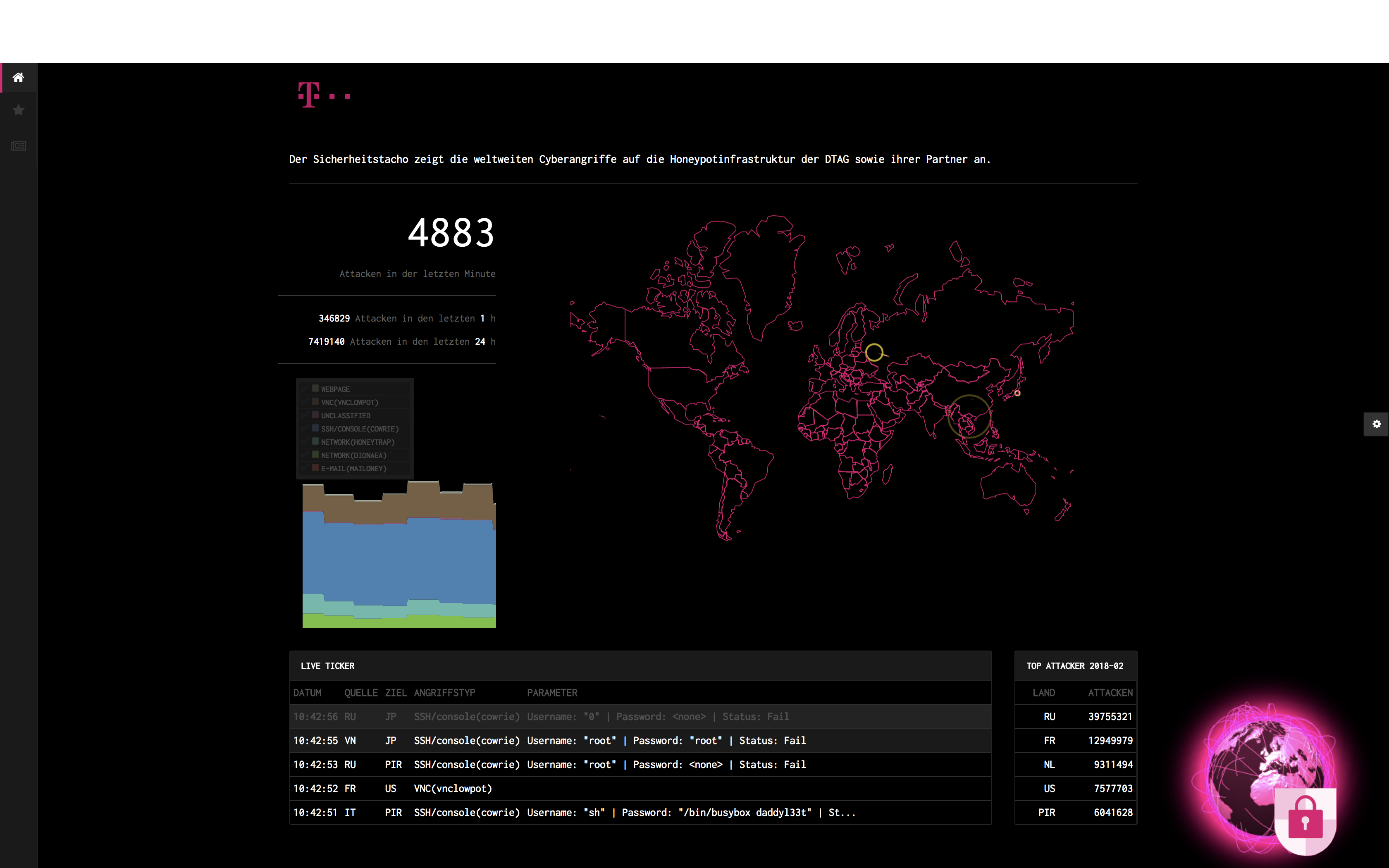

We also took the device to Cebit in 2013, to complement what we had developed for the last few months: our security-dashboard http://sicherheitstacho.eu. Meanwhile, we continuously expanded the install base of our honeypots and finally captured up to 800.000 attacks per day. We did not want to sit on the data but do something useful with it. So our backend developer Lutz came up with the idea to visualize the data and put it on a world map. We used honeymap, a world map framework from the Honeynet project, and visualized our data on it. When we launched it during Cebit, we got incredible public attention, both by the media, as well as the community. While I was attending Cebit with Markus, my other colleagues had to scale up the servers in the backend as they could not hold up against the load from the public.

As much positive feedback as we received, we also got some criticism, which we totally understood. It did lack detailed information on the attacks. However, the map was never intended to be an expert tool for security professionals, it was an awareness tool, an eye-opener, that’s why we showed it at a business fair. We had our own backend application for research and statistics, however not public. But internally, we had many discussions on where to go from there…

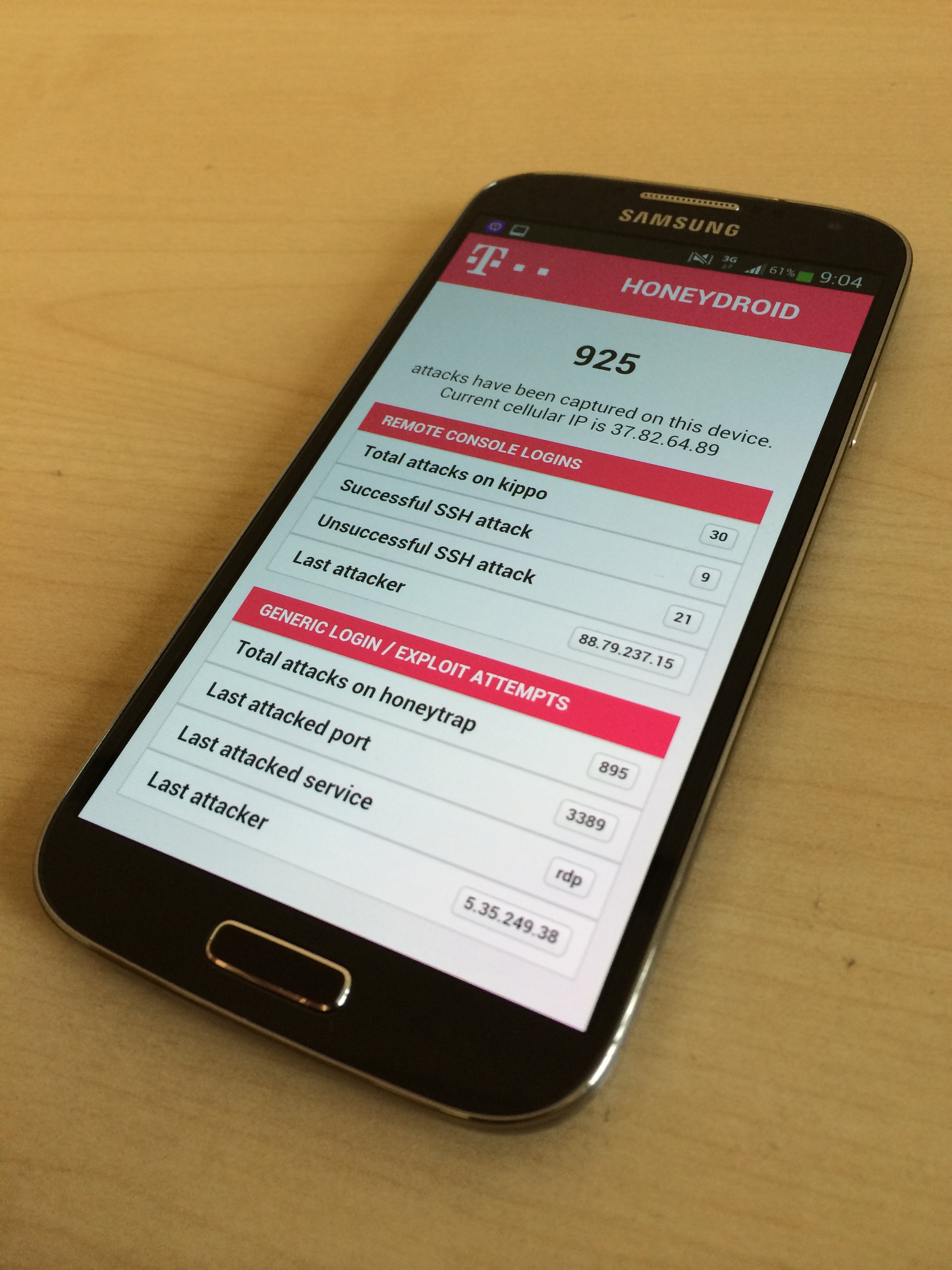

The success of the launch of the sicherheitstacho.eu brought us to showcase at many other locations such as DTAG’s public shareholders meeting and other interesting locations abroad where we could explain what we were doing and show the benefit for DTAG. In addition to public talks at conferences and some TV documentaries on cyber security (yes, it helps to visualize something in an easy to understand manner ;) ), we also got some press coverage on new developments, e.g. on our honeydroid, a smartphone honeypot running natively on Android smartphones in the background, a successor to the smartphone honeypots from 2011.

During Cebit’13, a member of the board requested that we would implement honeypots located at all subsidiaries of Deutsche Telekom. Hence, we had the task to create a scalable solution for honeypot deployment. We immediately thought of the Raspberry Pi solution and followed that path. It was then, when Marco (@t3chn0m4g3), the brainchild of T-Pot, joined our team. Marco and I created a preconfigured SD card, which would bootstrap and register at a puppet server for configuration management. Finally, we assembled and sent out 100 Raspberry Pis to the subsidiaries and asked them to connect them to a public IP. Like this, we had a scalable solution for adding and managing new honeypots. Within a couple of weeks, we could increase our honeypot install base to 180 sensors and had a broader look at the attack landscape on the internet, even more globally distributed.

In order to achieve a streamlined attack data submission from all the honeypots to our backend, my other colleague Markus (@trixam) created the data submission tool ewsposter, which extracts the relevant attack information from the log files, normalizes data, formats it as ews xml and submits it to our backend. In the future, we simply expanded this tool to support new honeypot types which saved a lot of time and created comparable attack statistics. In addition, this year other colleagues contributed with a rdp honeypot “rdpdetect” and a first cvemapper plugin for honeytrap and glastopf. 2013 was a very busy year for this small team of enthusiasts.

In the beginning of 2014 I refined the Raspberry Pi Honeypot “semtex” with a touchscreen display and some fancy looking UI. I built several of these devices and we made sure that every C-level executive at DTAG received one and knew about this small device. My personal highlight was when our new CEO Tim Höttges showed it to our then Minister of the Interior, Thomas DeMaizière, during a visit to our new CERT premises.

This year, we did not explicitly show any new stuff at Cebit. But we were present and showed some minor advancements to our sicherheitstacho.eu, which included some more comprehensible statistics and timelines, as well as the new RPI Touchscreen Honeypots, which were a good opener to a conversation. However, in the background we did not stop improving the tools we created.

Although we had the central management for our new herd of honeypots using puppet in place, the Raspberry Pi-based Honeypots were more care intensive than we initially thought. SD-cards were running out of inodes during operation or simply dying caused by SD-card corruptions, so we had to reevaluate our possibilities running and maintaining our fleet.

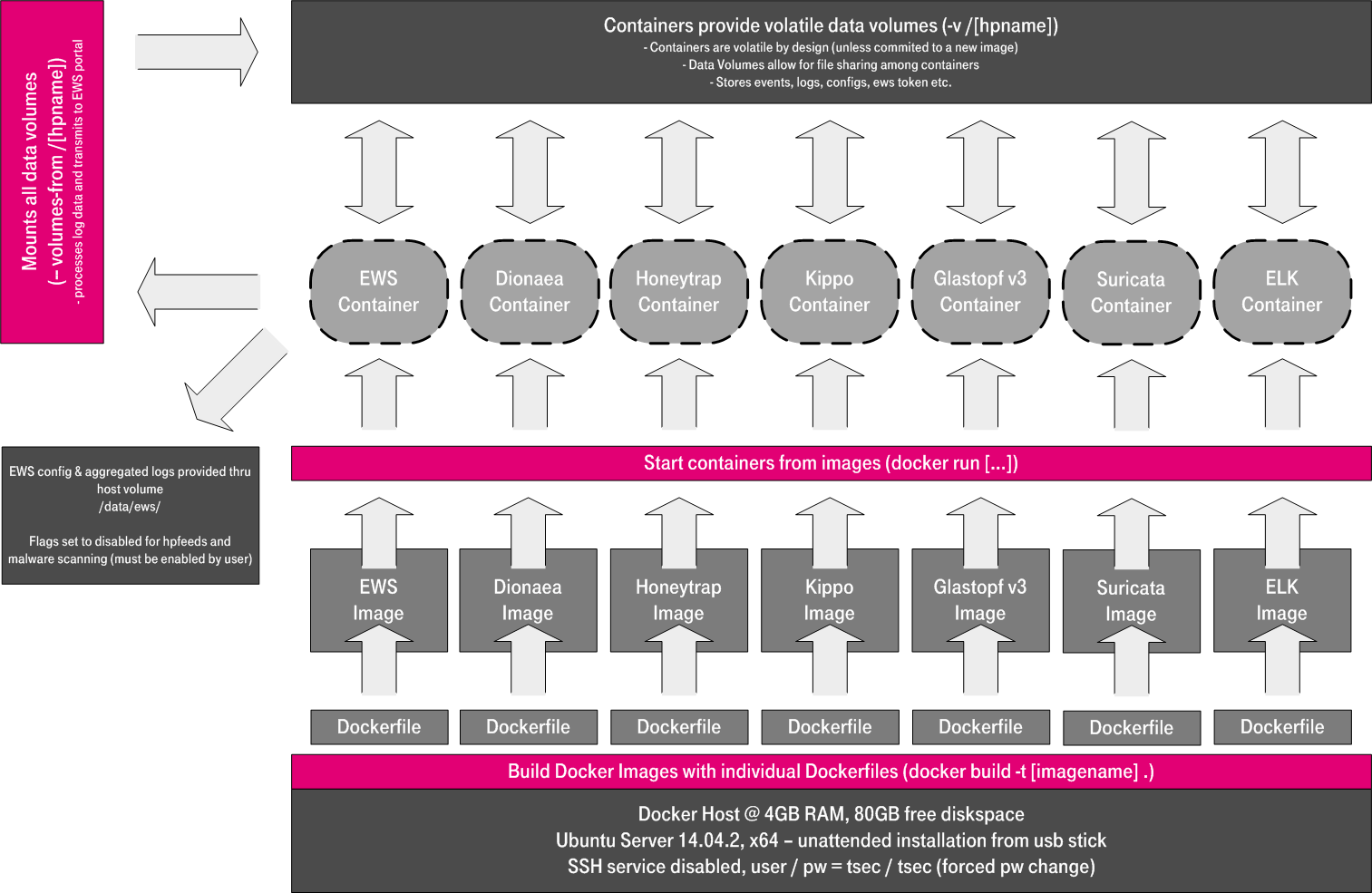

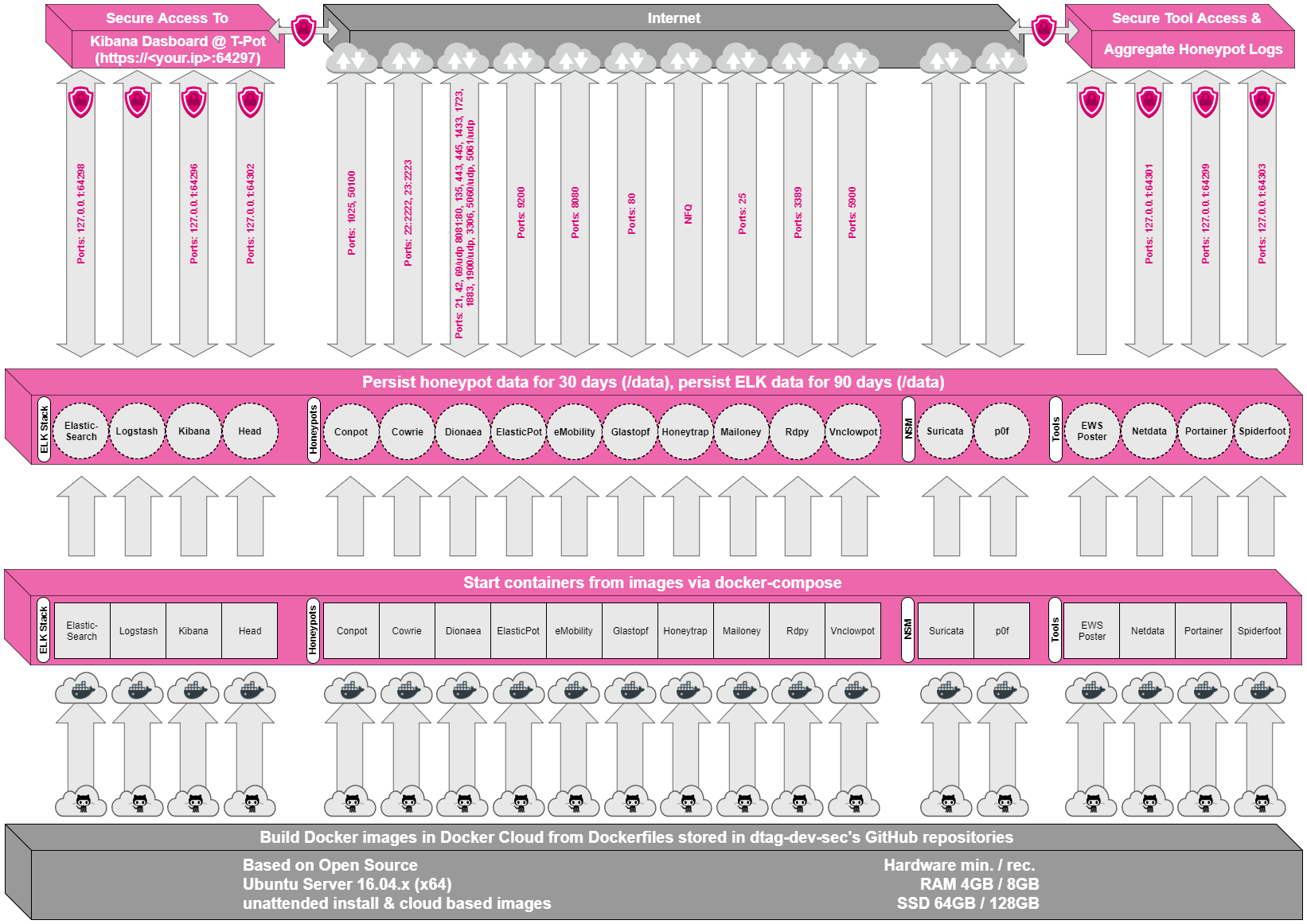

Fortunately, it was then, when docker emerged as the new kid in town for encapsulating and managing microservices. And it seemed to solve many problems we had running and managing our honeypots: Falling back to a safe state, different library dependencies, concurrency and data visualization. We started creating “honeyNUC” because the Intel NUC platform was our hardware replacement for the Raspberry PIs. We started dockerizing the honeypots with their individual software dependencies and were amazed by this technology and the possibilities we had. We could then orchestrate different honeypots, run them in parallel and route traffic from the host to the most suitable honeypot daemon. On top, Marco setup an ELK stack and created some cool visualizations. We got the permission to work on it a day per week, but many, many hours privately spent went into it - especially from Marco. Eventually, the result was T-Pot, which we decided to publish in 2015 as open source to honor all the community work which we depended on. And we made sure you could build your own custom ISO image for installation and run it as VM next to almost any x86_64 hardware.

This year, we also got invited to officially join The Honeynet Project. We were and still are honored to be able to contribute to this community.

So, we presented T-Pot to the public for Cebit’15, when we felt it was mature enough, but we still had a long list of improvements. Next to the initial release of T-Pot 15.03, we created a github project webpage to share our tools and news on the “DTAG Community Honeypot Project”. The response to T-Pot was great. The setup and operation of multiple honeypots can be a complex and time intense task. With T-Pot, we had a solution which worked “out-of-the-box” and had an install time of less than 30 minutes. Our developments even granted us the opportunity to present it at the Annunal Honeynet Conference in Stavanger, Norway. I won’t get into the details of T-Pot here, as there are extensive posts available that cover the latest features of each iteration of T-Pot and Marco created very nice videos for the setup etc.

Back then, the setup of T-Pot required an installation from an ISO, which was based on Ubuntu. In some cases, e.g. for cloud deployments, an ISO installation was not always feasible. So, I derived a script from the T-Pot ISO which would allow T-Pot installations in cloud environments based on Ubuntu such as Amazon EC2 and gave it the boring name T-Pot Autoinstall. Installing with the autoinstaller was even faster, and turned an Ubuntu cloud instance into T-Pot in less than 10 minutes. Nowadays, whenever there is a new T-Pot release, I try to adapt the autoinstaller to the new T-Pot version, too.

In 2015 we installed our first internal Honeypots in the DTAG corporate network and developed some new own honeypots like e-mobility, the simulation of a car charging station by our colleague Muhammad (@msbeiti), which is part of T-Pot’s “Industrial Edition”.

In 2016, T-Pot was updated twice in order to reflect changes in docker orchestration (e.g. move to systemd) and support new honeypots like our own elasticsearch honeypot elasticpot. Frequent feature requests like data persistence were addressed and overall improvements were applied. As Markus (@schmalle) likes to play around with new technologies, he also created some very specific honeypots like nodepot and puppetpot.

Meanwhile, we had around 3 Mio events per day captured in our honeypots. So, it was time to do some analysis. We handed over a large part of our data to T-Labs, the research branch of Deutsche Telekom, who analyzed the data together with the Ben Gurion Univerity, Tel Aviv, applying some machine learning techniques. The results were very interesting, however too much to cover here. One of the lessons learnt here was, that we needed to improve the normalization of our data and make data of different honeypots more comparable.

It is also notable that in May 2016, we joined a consortium well-known players to set up a European honeypot network, called SISSDEN, the “Secure Information Sharing Sensor Delivery Event Network”, funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, where Markus, Marco and I now contribute to. We are now half-way through the project and a lot of exciting work is done here, which I cannot spoil. Make sure you keep an eye on the SISSDEN website.

The year 2017, again, was a busy year for all of us. We improved Elasticpot, updated ewsposter to support various new honeypots and finally released T-Pot 17.10 with many, many improvements like smaller docker images based on Alpine Linux and new honeypot daemons like vnclowpot, rdpy and mailoney. It also featured an improved, faster installation procedure, lower maintenance, an update functionality, docker management tools and incident research capabilities. Overall, this seems to me like the biggest T-Pot release yet.

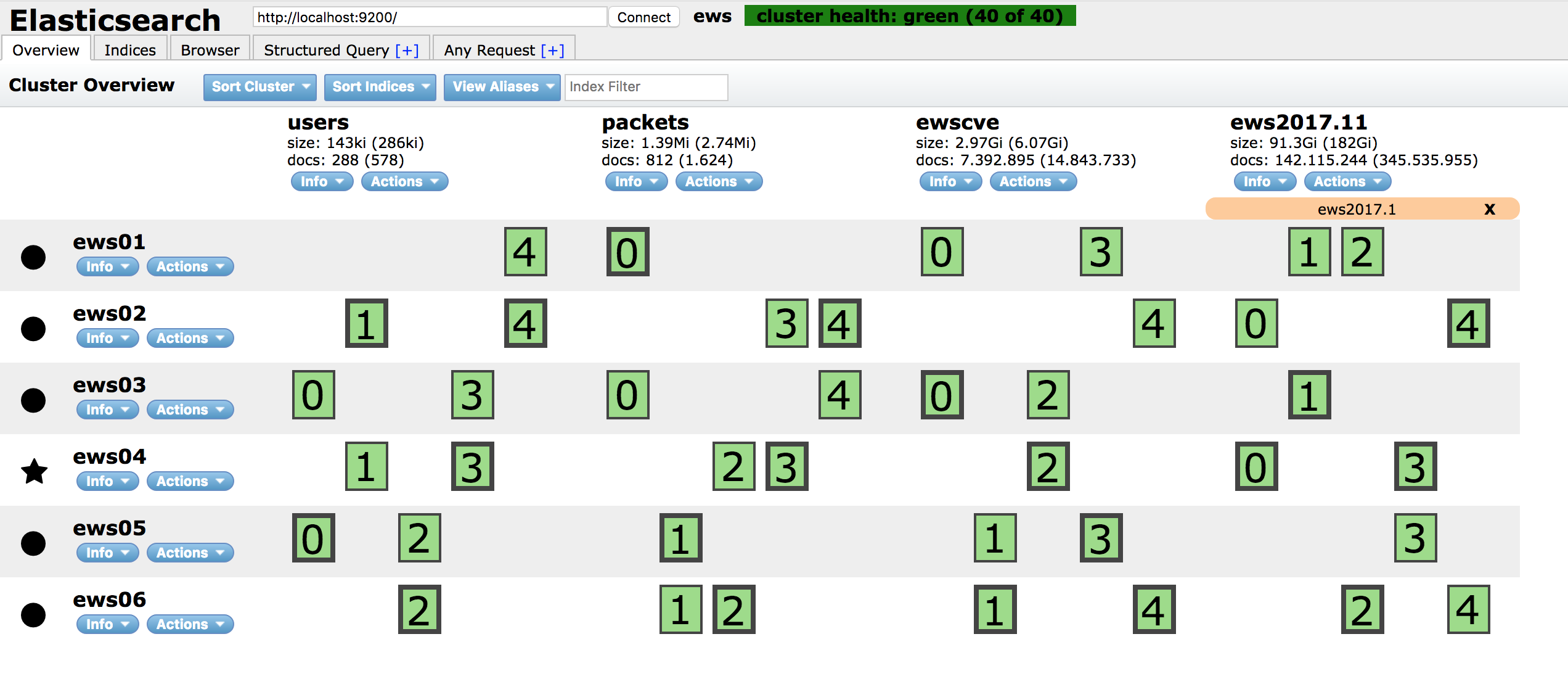

As if this wasn’t enough, we tackled a topic we have been neglecting the last years: the backend. As previously mentioned, the backend was initially developed in 2011 and improved until 2014. However, as Lutz, the backend developer was no more available to our project team, we could not modify the backend to great extent, due to the unavailability of a grails developer. We sometimes had to work around the limitations of the backend. So, eventually we decided to rewrite the backend and host it in our own cloud, the Open Telekom Cloud (OTC).

I started in summer 2017 implementing a feature equivalent API in python using Flask. Next to our production environment which held the data of our own DTAG honeypots, we had a second index running which contained the data transmitted by the community T-Pots. After Markus implemented the corresponding PUT-API, the endpoint that ewsposter sends its ews xml to, we had reproduced the basic APIs for the community index. One API to retrieve data from Community T-Pots and one to query the data stored.

At the same time, my colleague Aydin(@aydinchavez), who recently joined the team, redesigned the sicherheitstacho.eu using fancy reactjs client side javascript to query the data available. Initially, he queried the old APIs available, but was very limited in what he could display. So, we changed his endpoints to the newly created API. We talked about what data would make sense for him to display and we agreed on several new APIs he would need to query and I implemented them. As a follow-up, we merged the PUT and GET API in one single backend software component, we now called PEBA. We had a tight schedule and worked day and night trying to match the deadline of the opening of Telekom’s of the new Cyber Defense Center and show our new sicherheitstacho.eu dashboard on a large scale.

But the work did not end here. Long story short: After adding a caching mechanism and solving some other technical challenges, we finally switched our own honeypots to the new backend. Just in time for the fresh T-Pot 17.10 release. It was all very agile. I cannot possibly imagine what an open heart surgery is like, but this definitely felt like such an operation, and I am glad to say: the patient is alive. No major complications. :)

For those interested in operational aspects, we now have an index distributed over six Elasticsearch nodes, the API is currently processing between 5 and 6Mio alerts per day with a pretty low load. Our entire deployment is done via Ansible, so we can dynamically add and remove nodes to our cluster in the Open Telekom Cloud as we need.

Aydin, Robin (@rverton) and I are currently working on statistic functions and analyses so we can improve our analysis capabilities and Markus implemented the missing notification module. Step by step, we will reproduce the functionality needed and add features. The latest addition is the central storage of dionaea captured malware and honeytrap’s TCP attack payloads collected.

To sum it up, in the past, many people who ran multiple T-Pots requested some kind of central component. So here it is, PEBA, our own solution, tailored to our own needs. Feel free to contribute or let us know about your individual requirements. Maybe they would be of value for us, too.

Let me finish this post with a short anecdote: Just a couple of weeks ago, I installed ten new honeypots on our Open Telekom Cloud. Our honeypots played a key role during the investigation of a new mirai-variant wave on Dec. 5th. Just one hour after the wave of exploitation attempts was disclosed to us, my team mates Robin and Björn (@justsly) and I were able to identify and retrieve the 0-day Huawei exploit from our honeypots, reverse-engineer the malware and identify the C&C servers. We could then hand everything over to our operational CERT team. We are very proud to confirm that in this case, the Early Warning System using our honeypots worked. Even when we had to sacrifice our team’s Christmas party, it was a lot of fun. :)

In my opinion, this project is an example of great team spirit and collaboration. It is very agile and the focus shifted multiple times during the project. Initially, we were granted time as a “one-day-a-month” project. However, the efforts greatly exceeded the time given. Many hours of our own spare time went into this project but it was always supported, by our families and friends, as well as our employer. I would like to acknowledge that it would have never been so successful, if it hadn’t been embraced by all layers of our management: our team leads, Markus as vice president and the management levels above up to the board of directors of Deutsche Telekom.

Thanks to everyone supporting this project and keeping it alive, especially to our pot herders @schmalle, @trixam, @t3chn0m4g3, @aydinchavez, @rverton, Rainer, Daniel, Norbert, Ralf, Lutz, but also to our external supporters like Tillmann, The Honeynet Project, GDATA, Intel, all those I forgot.

And last but not least you for reading this and showing your interest.

Cheers // @vorband